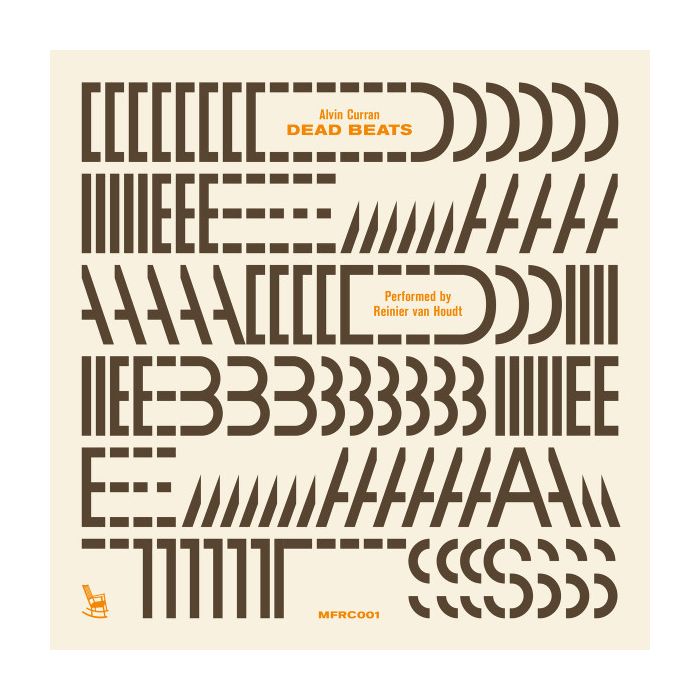

ALVIN CURRAN Performed by REINIER VAN HOUDT

| Artist | ALVIN CURRAN Performed by REINIER VAN HOUDT |

|---|---|

| Titel | Dead Beats |

| Format | 2x CD |

| Label | Moving Furniture Records |

| Country | Netherlands |

| Cat.-No. | MFRC001 |

In 2017 my dear friend Martijn Comes came with the idea to ask Reinier van Houdt to do a release for Moving Furniture Records.

After some emails between three of us we decided we would ask Alvin Curran to compose new work and so our first commission project started.

Now 1 1/2 year later we can present you the result with Dead Beats, composed by Alvin Curran for pianist Reinier van Houdt.

On the CD you will also find the composition Inner Cities No 9 ‘9-11-01’, which was Alvin Curran’s first composition after 9-11, also written for Reinier.

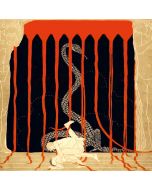

The album is presented as double CD and comes in lovely artwork designed by Rutger Zuydervelt and extensive liner notes by Tobias Fischer.

Read the full story behind the two different compositions below

About the album

Everything at Stake

Truth, multiplicity and the piano in the works of Alvin Curran and Reinier van Houdt

By Tobias Fischer

The piano has always been at the core of Alvin Curran’s oeuvre. Granted, you’d expect a statement like that from the liner notes to a collection of his piano pieces. In this case, however, he’s said so himself, in a candid interview with sound artist Andrew Liles: “It’s the focal point and kind of a totem for all my work in music.” Certainly, thanks in part to a cycle like “Inner Cities”, which spans twenty years of his career, it has become a sort of constant in a catalogue with very few constants, the perfect tool for a composer who likes to think beyond tools. Still, the bond between Curran and the piano has always been one of attraction and repulsion.

It was certainly where everything started. The piano was the first instrument Curran learned to play as a five year old son of virtuoso parents, stepping into the footsteps of a mother who accompanied silent movies and a dixieland jazz band trombonist. After studying with Elliott Carter, his path towards academia seemed paved. Rejecting this future wholeheartedly implied rejecting the piano as a symbol for the very tradition he had become to loathe. By the time the group of “long-haired, mad-eyed, stoned-out hippies” around him, Frederic Rzewski and Richard Teitelbaum had set up the Musica Elettronica Viva collective and were touring in support of their first big piece, “Spacecraft”, he considered the instrument outright bourgeois. It was a revolutionary thought at a time rife with revolutionary thoughts. When the MEV members had arrived in Rome just one or two years earlier, they only had one thing on their mind: “erasing our whole background”. That Curran eventually returned to the piano with the same fervour with which he had abandoned it is a tribute to his dedication to music rather than ideologies. Or, as he would later state: it was a manifestation of his belief that it didn’t matter how the music was made, but that it was made at all.

Rejection and Return

On “Spacecraft”, Curran still, in a sense, performed a ‘piano’. As if to mock his own classical pedigree, however, the instrument in question was a thumb piano mounted on a ten-litre motor oil can, whose sounds he picked up and mangled with contact microphones. “Spacecraft” felt like an alien attack on pretty much everything the establishment considered sacred. It was not just, as Curran himself put it, a music that no one had ever heard. It was music few classically educated listeners wanted to hear. When the MEV stopped off in Berlin, certainly not a city unreceptive to sonic experimentation, the audience’s reaction mostly consisted of hostile boos and furious verbal attacks, with some listeners purportedly jumping on stage to stop the show. In short: The effect of the music was overwhelming. After the collective’s members had renegotiated the borders between freedom and form, meanwhile, it seemed as though the demons inside of them had been pacified. Suddenly, everything was possible again, including a reappraisal of tools and techniques they would once have considered reactionary: Only a few years after “Spacecraft”, Frederic Rzewski had already returned to the grand piano and romantic harmonies.

Curran would follow suite not much later. But it was a gradual and quiet comeback. Even the momentous “Inner Cities”, started in 1991, began inconspicuously as a half hour long meditation over an A major chord, before growing into twelve moments and six and a half hours of music. Nothing is premeditated here, or at least not in the sense of there being an overarching concept. Daan Vandewalle may be the pianist most closely associated with the cycle, thanks to his integral performances. And yet Curran dedicated one of its most emotionally resonant moments, the moving 9th part, to Reinier van Houdt. The piece, as Curran explains, is the first of his compositions after 9-11 and, although not a political statement in any overt way, it does reflect on the relationship between the arts and life:

“The music in no way is meant to narrate those events. If anything it might contain some hint of the hopelessness of the contemporary arts and artists to confront tragedies of this proportion; and at the same time the need for artists to continue their own tragic/comic campaigns of hope and utopias which we all know are just around the corner.”

(label info)